Sandinista! isn’t the best Clash album, but it’s certainly the most fascinating. Despite being a Clash fan for so many years, I’ve never felt like I have a solid handle on it. I’ve also felt uncertain about its pecking order, apart from some obvious choice cuts and duds.

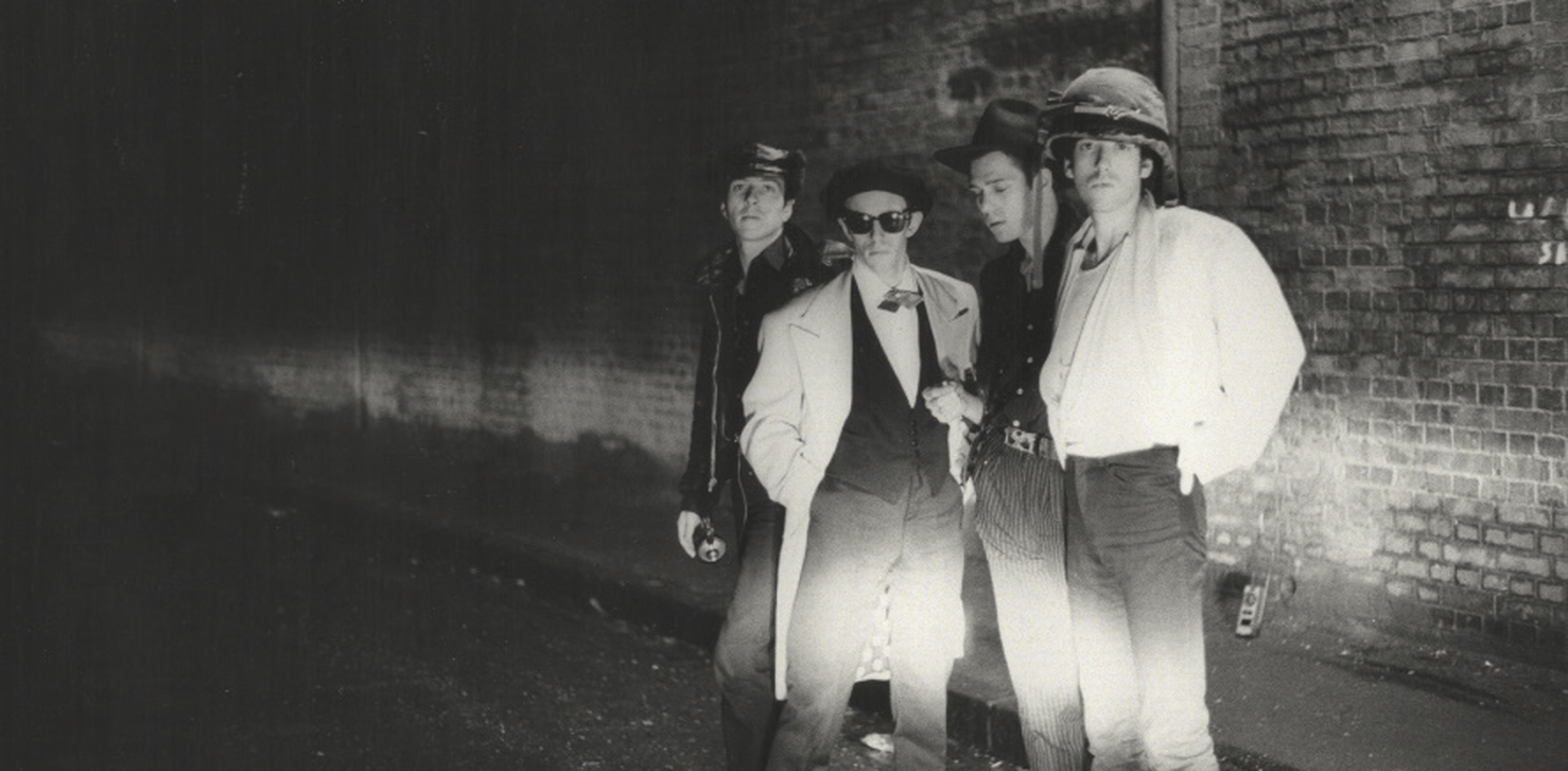

The Clash are my very favorite band, and each member – singer/guitarist Joe Strummer, guitarist/singer Mick Jones, bassist Paul Simonon, and drummer Topper Headon – are each individually among my very favorite musicians in their respective roles.

So in February, I finally embarked on a project that I’ve long envisioned – this article about Taylor Swift’s Lover was a sort of proof of concept – and asked a bunch of people to rank all 36 Sandinista! tracks. I received 35 ballots including my own, and this post details the results.

Thinking I could get away with the simple write-ups that I did for the Lover post was a mistake. I threw myself into my numerous Clash books, diving deeper into Sandinista! than I’ve ever dived into anything, and have ended up with a highly researched piece that blows past 20,000 words. Oops.

This post might have a bit more impact if, as I discovered after I began this project, Micajah Henley didn’t release a Sandinista! edition of the 33⅓ book series just last year, complete with similar data that he sourced from friends at the end of the book. The book is great, everyone go read it.

In his introduction, Henley writes: “Even die-hard Clash fans are typically split into two categories: those who believe Sandinista! is a masterpiece and those who think it’s an absolute mess that’s far too long.”

My position is, ¿por qué no los dos? I do prefer all three preceding Clash albums to Sandinista!, but while I think I’d regard a condensed version as a better album that might rival Give ‘Em Enough Rope or even their self-titled debut, I believe that the band’s legacy is incredibly well-served by the album being the way it is. I wouldn’t change history just to see another Clash album charge up the Acclaimed Music rankings, tempting though that may be.

However. I am a busy man. I do not always want to spend nearly two and a half hours with an album, especially when the album itself even seems to structurally concede that there’s a point at which it wouldn’t be offended if you decided you were done.

So I could do what a normal person might do. I could choose my favorite 12/15/20/24 songs and make a mix. Most sane people would take that route. But I love a consensus document.

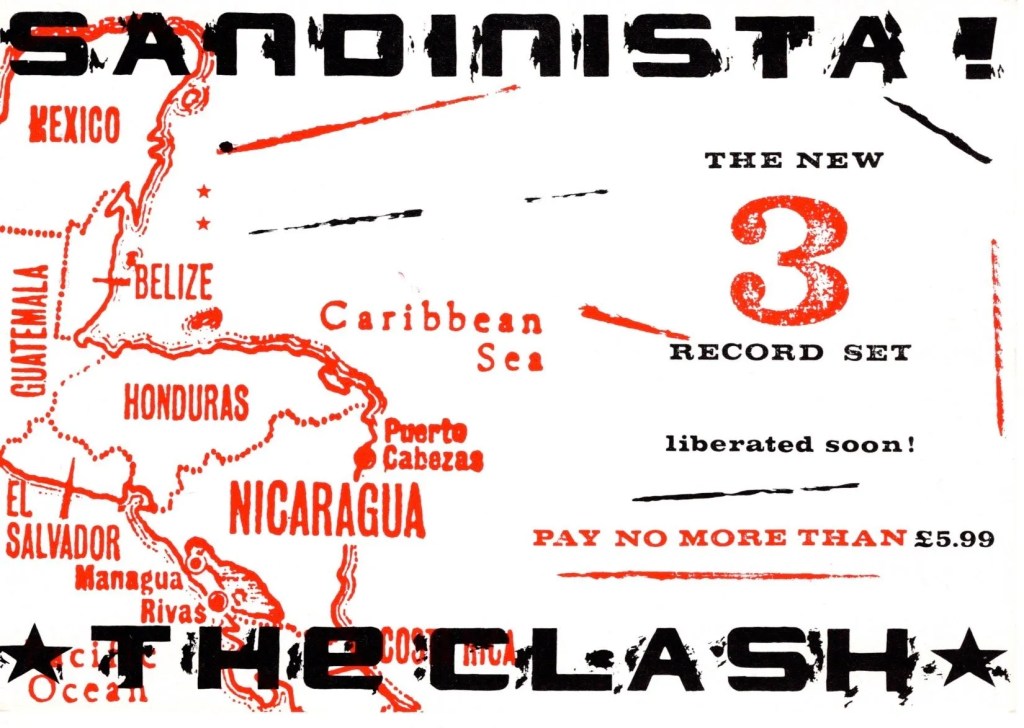

The Clash released a condensed promotional LP called Sandinista Now! that contained only twelve songs (hereafter I will refer to anyone’s top twelve songs from this album as their Sandinista Now!), but Sandinista Now! isn’t terribly satisfying. Firstly, it overemphasizes the beginning of the album, keeping all five of the first songs. More importantly, it has some serious oversights, leaving out #10, #9, and even #7 from the ranked list below. If there was a more recent official release that abbreviated Sandinista!, I could imagine looking to that. But not only will that not happen, it sounds like a rather awful idea. And it just makes thematic sense that the true abbreviated Sandinista! would be built by the people.

Micajah Henley’s 33⅓ ends with Henley and eight friends and colleagues each listing out their own personal Sandinista Now! lists. Throughout this feature, I will be noting how many of these lists each song was included on. This whole feature is really an (unintentional) extension of that exercise, simply with more voters and getting all songs ranked rather than an unranked top twelve.

This post will count down the 36 songs from worst to best, as voted on by the people, and will end with a few playlists that attempt to satisfyingly abridge the album.

First, a couple of notes. The Clash actually recorded 38 songs for the album. There’s little Marcia Gallagher’s performance of “The Guns Of Brixton” from the end of “Broadway” (I actually had a request to include this on the ballot). And, in fact, the dub version of “The Crooked Beat” was its own separate thing, but instead was merely appended to the original. The band kept these recordings on the album while preserving the symmetry of six tracks on each side. I could have maybe asked about these, but I was already asking a lot of each voter. “The Guns Of Brixton” seemed too brief, and most people simply accept that “The Crooked Beat” has a dip in the middle.

Finally, the information herein can be broadly found in Keith Topping’s The Complete Clash, Micajah Henley’s 33⅓, Martin Popoff’s The Clash: All The Albums All The Songs, Kris Needs’ Joe Strummer And The Legend Of The Clash, Pat Gilbert’s Passion Is A Fashion: The Real Story Of The Clash, Chris Salewicz’s Redemption Song: The Ballad Of Joe Strummer, and The Clash’s The Clash (which I will helpfully refer to as “the Clash book”). I’ll explicitly note whenever I’m actually taking something from one of them. Keith Topping’s The Complete Clash, Pat Gilbert’s Passion Is A Fashion: The Real Story Of The Clash, and Micajah Henley’s 33⅓ were especially helpful.

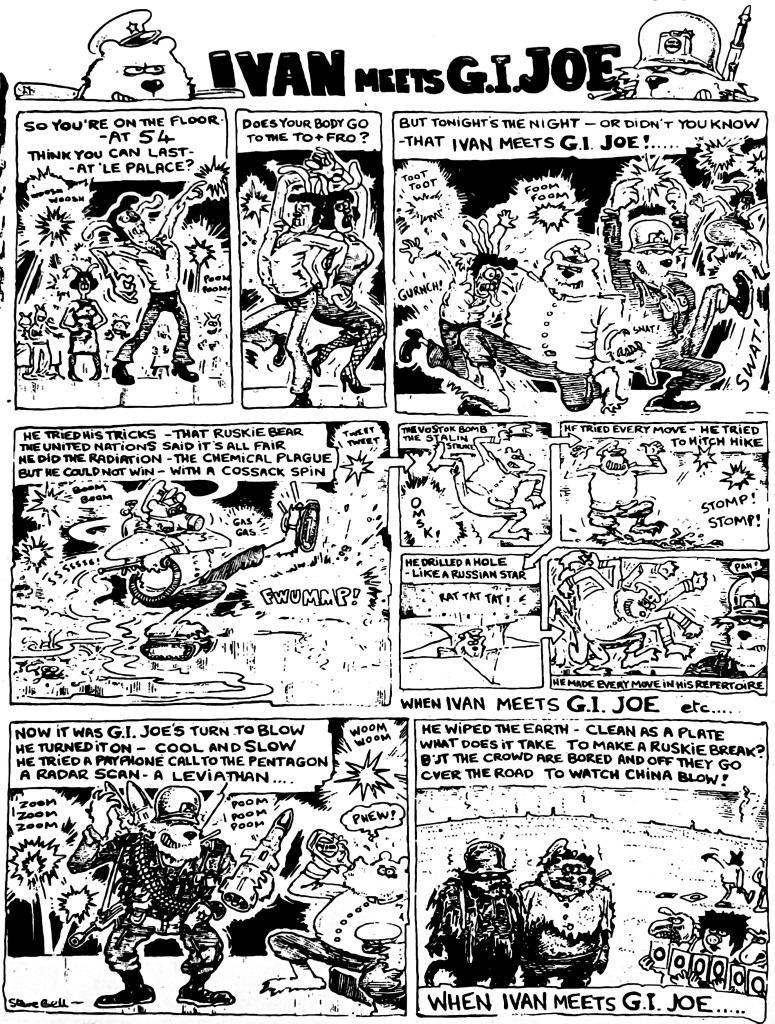

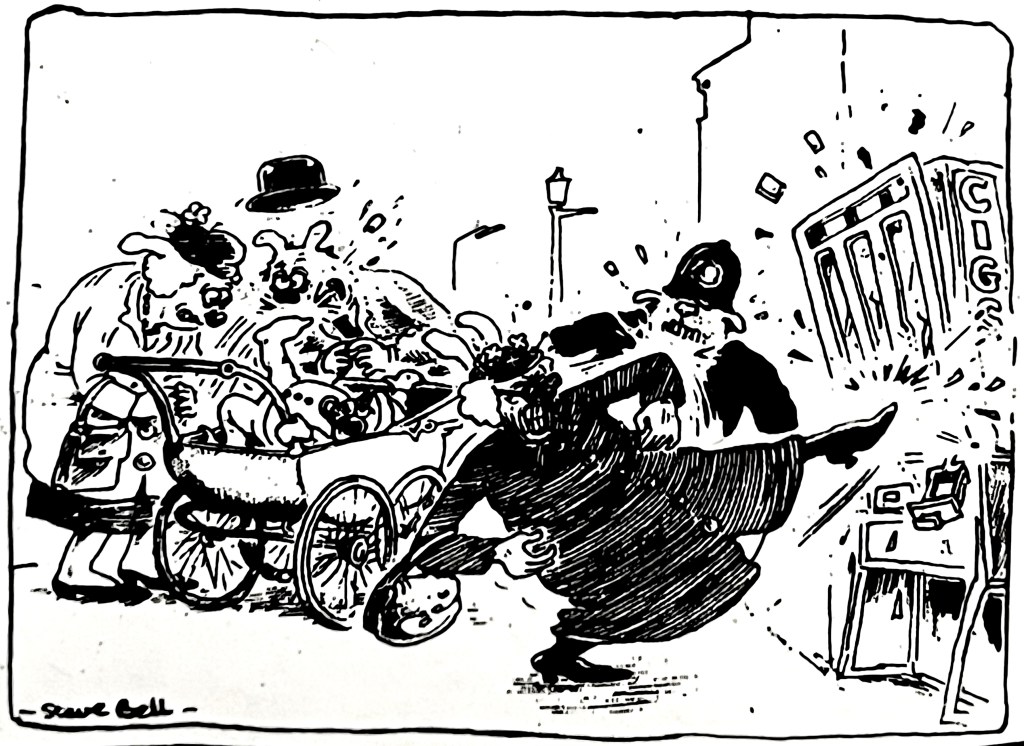

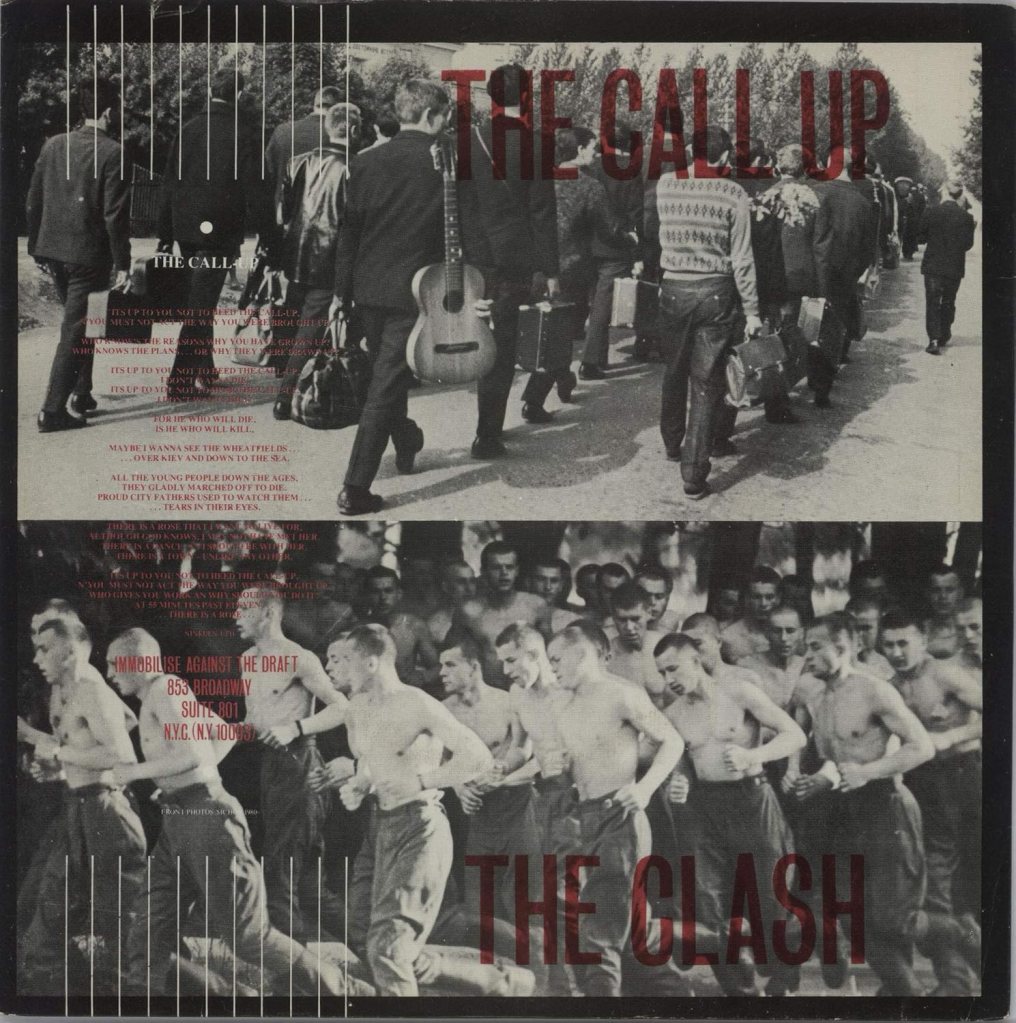

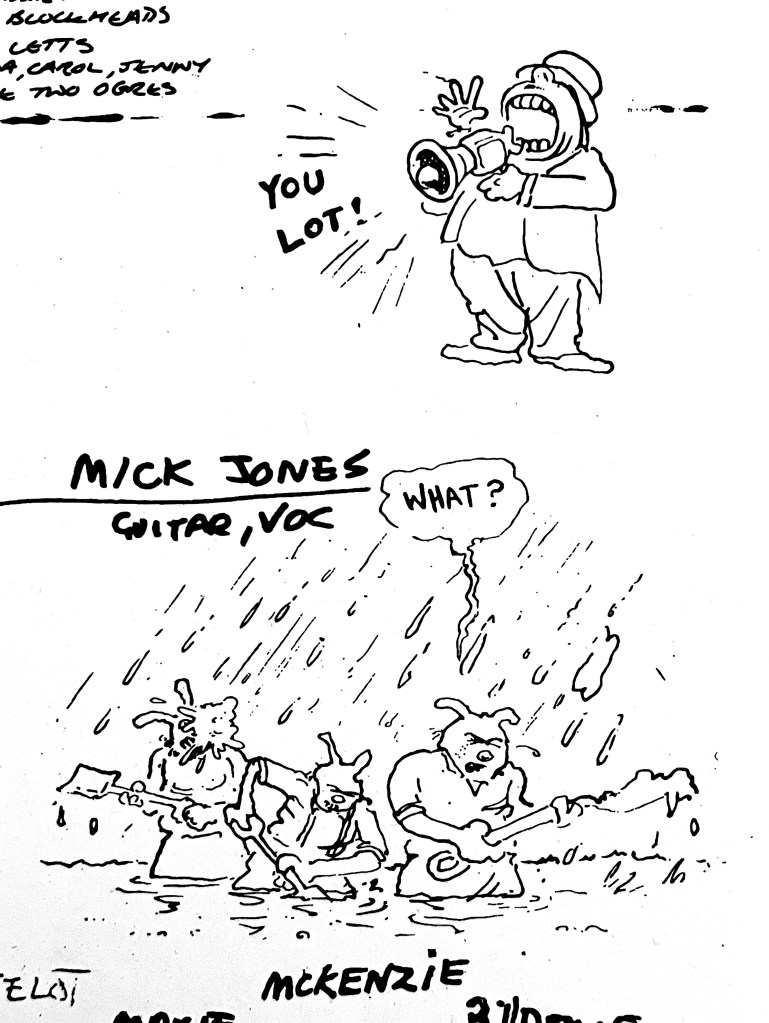

The cartoons throughout are from the Sandinista! insert “The Armagideon Times No. 3,” art by Guardian cartoonist Steve Bell.

I can’t tell you what to do, but my recommended experience would be to go through this article, listen to each song from the album as it comes up, and to listen to songs in YouTube embeds. Use your best judgment about whether to spend time listening to linked songs, but it’s often worth at least briefly checking out what I’m linking to.

Sandinista!

For London Calling (to my ears, the greatest album of all time), the band wanted to make a double album, but label CBS wasn’t into it. CBS did, however, agree to their request to release a free single with the LP. They also agreed the single could be a twelve-inch, and after the band had prepared enough music, the label had to relent to release London Calling as a double album for the price of a traditional LP.

The Clash wanted to run this trick back with Sandinista!, except as a triple LP. But CBS insisted that to do this, the band would have to forego royalties on the first 200,000 copies sold (effectively all royalties). The band paid dearly for their magnanimity to their audience, but it must have felt good to give their fans so much music for so little money.

Sandinista! remains one of the only landmark triple albums, as there are few truly major triple albums outside of live albums and compilations. George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, his 1970 album he released soon after his departure from The Beatles, was the first notable example. These days, a triple album requires three CDs rather than three LPs, and as such the only majorly notable examples since that transition are The Magnetic Fields’ 1999 69 Love Songs and Joanna Newsom’s 2010 Have One On Me. That these are the only four such albums so well-regarded is likely not just because of how rare the feat is, but because patience wears thin for lengthy albums. If you’re releasing three albums worth of material, you’d better have a good reason.

Following London Calling, the band hoped to release one single a month for a year, but when CBS wouldn’t release “Bankrobber,” that plan fell flat. After their US tour in March, the band was itching to record some music. They recorded a bit at Channel One Studios in Kingston and at Power Station in New York, both brief stays producing music that would eventually find its way onto Sandinista!, but their next move would reveal the way forward.

Sandinista! was essentially born from the band’s three week stay at Electric Lady Studios in New York City in April, 1980. There, the band would immerse themselves in American culture and politics and would collaborate with a wide cast of characters. There was Mikey Dread, their frequent show opener and their producer on “Bankrobber” who would do a large amount of production on the album. There was Mickey Gallagher, the keyboardist for Ian Dury And The Blockheads (a sort of punk-adjacent singles band) who was a vital player on London Calling and who would bring other Blockheads to these sessions: saxophonist Davey Payne and, very importantly, Norman Watt-Roy, filling in on bass for Paul Simonon while he was shooting a film.

Sandinista! was only partially written and recorded at Electric Lady, but those sessions in particular sound like they were special. The band’s three week stay was unplanned, and they spent long hours working. “We were in there for three whole weeks, day and night. I never went to a bar or a nightclub or anything,” Strummer recalled. “Every day we showed up and wrote phantasmagorical stuff.”1

As far as I can tell, every original word on Sandinista! (save for Tymon Dogg’s tune) is Joe Strummer’s. It’s likely other members chipped in lines here and there, but I can’t find any definitive proof. Even when Jones, Simonon, or even Headon picked up the mic, Strummer’s words were behind them. At Electric Lady, Strummer began the practice of holing up in his “spliff bunker,” an arrangement of road cases where he could seclude himself and write lyrics.

To Dread’s displeasure, the band took on production responsibilities, and this largely meant Mick Jones was producing. And while Strummer handled the lyrics, those were mostly turned into music by Jones.

Helen Cherry, who frequently accompanied Tymon Dogg, remembered: “I hadn’t realized what Mick was doing in The Clash, and I don’t think a lot of people did. But I was lucky enough to hear them record quite a lot of Sandinista!, and I was amazed to see that Mick was so much of an energy as a writer and an instrument player for The Clash.”2

Clash mixer Bill Price remembers the tenor of the Strummer/Jones dynamic at the time: “Their fights used to get really bad, and if they could maintain a musical relationship that was pretty much all that could be expected. Occasionally, it got so bad they couldn’t really even do that. If the musical relationship was intact, as far as the studio was concerned, we could work with that. Musical differences would escalate into political differences. The sound of a guitar note would grow until it represented capitalism for one of them and socialism for the other. It was never shouting matches. More like silences and withdrawals.” Price added that sometimes the two got along famously as well, and noted their dynamic “was best not poked at if you were working with them.”3

Also from Gilbert, Manager Peter Jenner recalls: “There was magic between Joe and Mick, a Lennon-McCartney thing. They complemented each other: the toughness Joe had and the musicality that Mick had. It was the friction between them that made everything interesting.”

With Strummer in his spliff bunker and Jones in the producer’s chair, Topper Headon also started contributing more. Though all writing was credited to “The Clash” as a unit (a new development from the previous Strummer/Jones paradigm), some sources include more detailed writing credits, and we can see that Headon earns a whole lot of them. Price remembers: “A lot of the songs were started as ideas by one or two people on bizarre instruments, quite a lot by Topper, actually. He’d wander over and find a marimba in the corner and play a little something which eventually became a song. That sort of thing. These ideas would grow. Topper would be raised into getting a drum track together, then every so often, miraculously, Joe would breeze in with a bit of paper and say, ‘I’ve got a few words to that,’ and before you knew it there was a song. Sometimes it would be re-recorded as a complete song with the whole band, and sometimes we’d carry on working with the original fragments. The whole process was made possible because Topper was such a fabulous musician.”4 This was all despite Headon’s worsening problems with addiction. Though he was getting less reliable, often not showing up at all, when he turned up, Headon’s musicianship and creative contributions were greater than ever.

When he returned to the fold, Paul Simonon also impressed. Headon recalls: “When I played with Norman Watt-Roy, he’d go off somewhere on the bass, I’d go off on the drums, and you sometimes didn’t know where you were. With Paul, he played so solidly you could just lock back in with him. I loved his bass playing.”5

British reviews of Sandinista! were brutal. The British music press had no patience for Sandinista!‘s self-indulgence, especially as they felt The Clash’s music was becoming too American. To this complaint, Strummer responded, “Who gives a shit whether a donkey fucked a rabbit and produced a kangaroo? At least it hops and you can dance to it.”6

Maybe they had a point, though, because Stateside, Sandinista! was yet another critical success, winning the 1981 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll over X’s Wild Gift and Elvis Costello’s Trust.

Sandinista!‘s legacy is as the bloated follow-up to one of the consensus all-time great albums, but it’s so vast that it feels so unknown. Sandinista! has nearly 40% of The Clash’s total album tracks (I’m leaving out Cut The Crap in the denominator, admittedly), but it feels like there are gaping pockets of the album that even I, as a bit of a superfan, have not yet investigated. It’s not just that Sandinista! has a peculiar legacy. It’s that the album is a great mystery.

In making so much music in so many different styles, in forcing themselves to grow from the three furious chords that dominated their early music, it’s not just that The Clash carved out a place in the history books for this behemoth album. It’s that this behemoth album was further carving out theirs, even as their furious addition weighed the album down.

Jones once said, “I always thought of it as being a record for people who were on oil rigs or Arctic stations, and not able to get to record shops regularly. It gave them something to listen to, and you didn’t have to listen to it all in one go, you could dip in and out. Like a big book.”7

The Filler

It’s often said that All Things Must Pass was a triple LP because Harrison had held back just so much material with The Beatles, but the third LP, titled “Apple Jam,” is, well, filler. Your mileage may vary, of course, but it’s not really true to say that Harrison had three LPs worth of songs bursting out of him. But All Things‘ legacy as a triple likely helps it, even if the enjoyment per minute levels are likely considerably lessened.

Sandinista!‘s third LP is similar. It does have a few real songs (including some absolute winners that we will get to much later), but side six in particular is dominated by dub “versions” of prior Clash recordings.

Dub is an offshoot of reggae that began in the late sixties and was developed by legendary names like King Tubby and Lee “Scratch” Perry. By the mid-’70s, dub music would take on an echoey aesthetic that we see on Sandinista!, and most reggae singles would have a dub version of the single on the B-side. Though it’s often thought of as niche, dub music was a vital part in Jamaican music during the seventies.

The dub tracks get a tough rap, mostly rightly so, but while they bog down Sandinista! as an album, the band disappearing into a very specific crevasse of Jamaican music feels like a great legacy-add, a reminder of just how committed they are to spreading music that goes so far beyond punk rock. Sandinista! is all about that, but it’s never clearer than on their commitment to dub.

The depths of Sandinista!‘s third LP might be a little less engaging than Apple Jam. This tier largely focuses on the album’s sixth side, but we do get a few from the fifth and a couple from the sixth do make it a tad higher. But Strummer once said of the album’s sixth side: “Only bold men go there.”8

36. “Mensforth Hill”

mean: 31.6

33⅓: 0

Rated dead last on an astonishing fourteen ballots, “Mensforth Hill” is the least beloved song on the album. “Mensforth Hill” manages to be the worst in my dataset by any metric. Indeed, it was my own #36.

“Mensforth Hill” is essentially “Something About England” played backwards with a few more bells and whistles. It’s sometimes called The Clash’s “Revolution 9” – Sandinista! is The Clash’s White Album, after all – but this is generous. “Revolution 9” is a bold swing, a pretty unforgettable experience that’s fun to talk about. “Mensforth Hill” is not really going to get any traction at your dinner party. And, following a couple of side five winners, it’s the first indication that Sandinista! is more or less out of gas.

Unlike the truer dub songs, Sandinista!‘s lyric booklet takes care to note that “Mensforth Hill” is an instrumental, then adds the note: “Title Theme From Forthcoming Serial.” I would love to be able to tell you about the existence of such a serial.

35. “Shepherds Delight”

mean: 30.4

33⅓: 1

Unsurprisingly, “Shepherds Delight” failed to engage our electorate. However, “Shepherd’s Delight” is the only song ranked lower than thirtieth to find its way onto any Sandinista Now! lists from Henley’s 33⅓. In fact, it’s Henley himself that includes it. His write-up of the, er, song doesn’t really try to make the case. Perhaps it’s just that any kind of Sandinista! without this kind of thing must be somewhat inauthentic and untrue. Fair.

Strangely, Sandinista! ends with two reinterpretations of songs from their debut LP. I have always personally yearned to unearth something satisfying from the triple’s finale, but this quiet dub over Simonon’s bass part from their stupendous cover of Junior Murvin’s “Police And Thieves” – some sources say it’s from “If Music Could Talk” or vice versa, but the bass lines don’t match so I don’t think so – never comes to life. Well, mostly. With about a minute to go, voices arrive: “Could it really happen?” “I hope not.” And then something horrible happens. Perhaps it’s a missile launching. Perhaps it’s a bomb exploding. We listen to it for the final minute of the album. All right, then.

“Shepherds Delight” was actually the first song recorded for Sandinista!, being recorded at the “Bankrobber” sessions with Mikey Dread.9

34. “Version Pardner”

mean: 30.4

33⅓: 0

Not a ton to say about “Version Pardner.” We are still in the middle of the five dub (or dub-adjacent) tracks on the album’s third LP, and while “Version Pardner” has beaten a couple of tracks, only one voter (of 35!) said it was their favorite of the six dub tracks. The most notable thing about “Version Pardner” is that it’s the longest of these dub tracks, adding thirty seconds to the already-too-long “Junco Pardner.” It also features the original vocals, starting and stopping them in a way that pleasingly reminds me of Neil Cicierega’s “Wndrwll.”

“Version Pardner” actually tied with “Sherpherds Delight,” but I gave the tie to “Version Pardner” because its 25th and 75th percentiles were each one better than those of “Shepherds Delight.”

33. “Junkie Slip”

mean: 29.6

33⅓: 0

Wait, a real song? Down here? We have a real song, folks! “Junkie Slip” breaks up the dub party. Indeed, “Junkie Slip” falls below one of the five from the third LP and decisively below another. Its mean is five full ranks worse than the next-nearest non-dub, non-remake track (see #29).

But “Junkie Slip” is fascinating. First, it’s a skiffle tune. The story of the American music scenes that led into rock and roll in the fifties are so enrapturing that I often forget that some kind of music had to have been popular across the pond in the fifties. The Brits were messing around with an old American genre, a poor man’s folk music called skiffle. I think what we were getting up to was cooler.

“Junkie Slip” is most notable because it is very likely about Headon’s heroin addiction. Headon was fucking up enormously enough that this not-particularly-subtle song was made and even gets into how he would sell his things to fund his addiction. The band managed for nearly two more years until they finally sacked Headon for his behavior, and the band would soon fall without that pillar. Interestingly, Headon is credited as a cowriter.

I don’t think the voters cared about all that. I think the voters just thought that Strummer yelping “junkie slip!!!” the way that he does is pretty annoying.

32. “Silicone On Sapphire”

mean: 28.6

33⅓: 0

Congratulations to “Silicone On Sapphire” for beating a real song. We are all very impressed. “Silicone On Sapphire” earns its place into the more-tolerated half of dub tracks, but it also earns the unfortunate distinction of being the one song that absolutely no one thought a ton of. Every other song here made some sicko’s top thirteen at least once. “Silicone On Sapphire” never made it better than anyone’s #17. Only two voters preferred it to the other five dub tracks.

Musically, this dub takes Sandinista! namesake “Washington Bullets” and sends into the future, or perhaps outer space. It sounds modestly neat. In The Complete Clash, Topping observes that “Silicone On Sapphire” could draw inspiration from Gary Numan, The Human League, or perhaps Hawkwind, contextualizing “Silicone On Sapphire” as The Clash’s take on a contemporary trend.

Throughout, Joe is mumbling some jargon about tech that is mercifully available on lyric websites. Ah, he’s saying things like “my prerogative is zero.”

“Silicone On Sapphire” is a bit of a Michael Ginsberg-style tech freakout named for silicon on sapphire, a semiconductor performance improvement technique. Hrm, “Silicone on Sapphire.” Do you think they were just mistaken and meant silicon, or do you think they were cracking a bit of a joke about cosmetic surgery? The answer is lost to history.

The Fluff

Thought it feels very safe to cut the material from the previous tier from an abbreviated Sandinista!, the next six songs, while still largely disposable, do have a bit more going on. Here we exhaust all but three tracks from the third LP and also get into the bottom three from the better-regarded first two.

31. “Living In Fame”

mean: 26.0

33⅓: 0

For reasons that elude me, #31 “Living In Fame” fared so much better than #32 “Silicone On Sapphire” that it deserves a line of demarcation to mark its superiority. Its mean is a full 2.6 better than that of “Silicone On Sapphire,” the largest gap in our results. Its mean is over 1.6 worse than that of our #30 song, the fourth largest gap in our results. “Living In Fame” is on an island and could be given its own tier. Perhaps it’s that there is a real song here, even if it’s rather weak and can’t break out of the failings of Sandinista!‘s dub material.

On this track, Mikey Dread actually adorns “If Music Could Talk” with a full vocal performance, though like on “If Music Could Talk” the vocal can kind of fade into the music. Dread is a prolific reggae and dub performer, producer, and radio host – his Dread At The Controls (also the name of one of his most notable songs) quickly became the Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation’s most popular program – who became friends with The Clash, opened many of their concerts, and produced their Sandinista!-adjacent single “Bankrobber.” After, his voice would find his way onto a ton of Sandinista!, and he’d later say that the label had unfairly deprived him of a producer credit for the album. Indeed, Dread produced large sections of Sandinista! and deserves both credit (and blame) for much of its sound.

Dread would keep making his own music – his 1982 track “Roots And Culture” is easily his most-streamed song – and would also collaborate with English reggae band UB40.

Here, Dread strangely takes his time with the mic to call out some of The Clash’s peers (especially 2 tone bands): The Selecter, The Specials, Madness, The Beat, The Blockheads, Sex Pistols, The Nipple Erectors, Generation X. All just to say that, in fact, The Clash are where it’s at. It’s honestly pretty weird.

The Nipple Erectors, often known as The Nips, were actually the first project of one Shane MacGowan, later of of Pogues fame. MacGowan was actually an early Clash superfan, and a photo in which he had a bloody ear at a 1976 concert of theirs resulted in cheeky headlines like “CANNIBALISM AT CLASH GIG.”

Generation X, fronted by Billy Idol, also included guitarist Tony James – who would go on to form Carbon/Silicon with Mick Jones in the 2000s – and former Clash drummer Terry Chimes.

Concerning songs the layman might be aware of, after the recording of “Living In Fame,” Generation X would go on to release “Dancing With Myself” – which would effectively launch Billy Idol’s solo career – and Madness would go on to release “Our House.”

Given that The Blockheads were name-checked and three of those guys played extensively on Sandinista!, these call-outs were likely all in good fun.

30. “Career Opportunities”

mean: 24.4

33⅓: 2

The very hardest thing about ranking Sandinista!, for me, was figuring out what to do with “Career Opportunities,” in which Mikey Gallagher’s boys Luke and Ben sing that song – in my estimation one of the band’s ten or so very best – from their debut album. The voters felt the same way, and “Career Opportunities” has the very highest standard deviation of any song here. Voters had it as high as #2 and as low as #36. Its middle 50% has a huge span from #16.5 all the way down to #33.

Gallagher remembers, “What happened was, I was doing Blockheads sessions from ten in the morning, until about nine at night, have a break, and then I would go up and do the sessions at Wessex with The Clash, and I would take my family up. The kids would sleep there and everything.”10

So, what to do with an inferior but charming version of a great song? First, let’s take stock. Gallagher’s harpsichord sounds deliriously gleeful, a pretty funny contrast to a song about the horrible reality that so many of us have to grow up to do things we don’t want. It, along with his children’s mini-choir, makes this sound like something parents might throw in the tape deck to get their two-year-old to settle down during a short drive. The most cynical Raffi song ever.

My favorite part of the original “Career Opportunities” goes “I hate the army and I hate the RAF/I don’t want to die fighting in the tropical heat/I hate the civil service boom/I won’t open letter bombs for you.” God, it’s so good. Here, they excise the former half entirely and change the latter to “I hate all of my school’s rules/They just think that I’m another fool.” Fair enough, but quite a downgrade.

Later in life, Ben and Luke Gallagher had a rock band called Little Mother. There’s scant information about the band, but they were signed to Island Records and put out an album called The Worry, on which Ben played guitar and Luke played bass. It’s hard to tell with how little information is out there, but it seems like Ben was their lead singer and songwriter. Their only release activity was in 1999.

I had “Career Opportunities” a bit higher than the mob, up at #25. My old shortened Sandinista! playlists would often include it, just to throw in a bit of the true Sandinista! experience.

29. “The Crooked Beat”

mean: 24.2

33⅓: 0

“The Crooked Beat” does not fare well. It manages to beat all of the third LP experiments, but I actually had “The Crooked Beat” below several of those, all the way down at #34. While the dubs don’t engage me much, “The Crooked Beat” is an active irritant. It’s also over five minutes, one of the longest songs on the entire album.

A pretty lazy take on British nursery rhyme “There Was A Crooked Man,” “The Crooked Beat” – Paul Simonon’s love letter to the reggae he listened to in his youth, Simonon was the one who had led The Clash into reggae – is enormously disappointing for anyone expecting Simonon’s next song after London Calling highlight “The Guns Of Brixton” to be similarly satisfying, or really of any value at all.

Simonon was actually away from the band for an acting role in something called Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains – in which Simonon plays a member of fictional band The Looters – so The Blockheads’ Norman Watt-Roy took over bass guitar duties on quite a few of the album’s best songs. Some have said that “The Crooked Beat” was an effort to get Simonon more royalties, with his only other writing credits on the album being “If Music Could Talk,” “Rebel Waltz,” “Broadway,” “Living In Fame,” “Career Opportunities,” and “Shepherds Delight.”

In a way, we still haven’t escaped the dub dredges of the album. Halfway in, Mikey dread announces: “Wahhhhh! It’s a bird, it’s a plane! No, it’s a dog-wise stylee!” And then “The Crooked Beat” repeats as a dub version of itself. No! Why!

28. “Version City”

mean: 24.0

33⅓: 1

“Version City” certainly has its fans, and that’s why it’s as high as it is. However, its median rank is strikingly low, lower than that of “The Crooked Beat,” “Career Opportunities,” and even “Living In Fame,” with its median ranking falling at #28.

“Version City” is a perfectly competent R&B-style track that seems to reference a great musical tradition that you can climb aboard, that all the great bluesmen have ridden. I’m all for the self-mythologizing Clash tracks and for them painting themselves as inheritors of the great musical tradition, but the ideas in “Version City” seem a little half-baked and half-hearted to me. “Version City” might deserve higher than #28, but it’s hard to justify it leapfrogging over many songs currently above it.

The song is largely about that train, which is merely at Version City. It’s hard to parse what exactly Version City itself signifies here. Notably, “version” commonly refers to dub tracks. It’s as if “Version City” is a fun introduction to the mad world of Sandinista!‘s sixth side. Now entering Version City. Perhaps they were merely out of gas by track 31, but maybe voters actually recoiled at “Version City”‘s announcement of what was still to come.

The highest vote for “Version City” is a #7 vote from one Noah Biasco who notes that he boosted it because it “invented” the beat that runs throughout LCD Soundsystem’s landmark 2002 single, “Losing My Edge.” It’s a pretty astute observation, as I’d never noticed and can’t really find mention of the similarity on the internet. The opening beat of “Version City” does actually resemble and predate the Casio “PT-30 Disco 2” demo track that “Losing My Edge” lifts its beat from (actually, “Version City” uses a different built-in demo from a keyboard. Optigan’s “Singing Rhythm” backs up the intro and outro). Whether the folks at Casio actually ever made it to side six of Sandinista! is anyone’s guess.

27. “One More Dub”

mean: 23.0

33⅓: 0

I wouldn’t call “One More Dub” “controversial,” exactly. While it has the poll’s fifth highest standard deviation and appears as high as #4 and as low as #35, I doubt it’ll start many arguments. It’s easy to see that while some might regard it as yet another indulgent, essentially lyric-free track that’s apiece with the end of the album, fifteen voters regard it as the best of the dub tracks, making it the overwhelming favorite. I had it at #22, making “One More Dub” one of the four tracks I think is most underrated by this list. But I’m not losing sleep with it at #27, either.

It’s easy to see why this dub track is the most well-received. “One More Time” is a showcase for drums and bass guitar – this is again Watt-Roy in place of Simonon – the way the other adapted songs just aren’t, creating a genuinely cool moment when the top of the song flies away and we’re just left with a bottom that would sound pretty great booming from a sound system.

26. “Look Here”

mean: 22.8

33⅓: 0

We’re done with the dubs now, but I think people can still sense the covers even if the songs aren’t all that famous. Sandinista! has three cover songs – we’ll get to one of them much later – but the other two, “Look Here” and another coming very soon, don’t figure high into the rankings of real songs.

Mose Allison was a jazz pianist notable for his use of blues, and his most enduring legacy might be that rock artists took notice. Most famously, The Who opens Live At Leeds (not the more common expanded editions, the six song original!) with his “Young Man Blues.”

Strummer had actually performed “Young Man Blues” with his earlier band The Vultures, but covering “Look Here,” from Allison’s 1964 album The World From Mose, was unsurprisingly Headon’s idea. Headon recalls of his 1977 audition for the band: “Mick, Joe and Paul hated funk and they hated jazz and anything that wasn’t punk. At the audition I went to there were five other drummers and they agreed with everything Mick, Joe or Paul said. When they asked me ‘What are your favorite drummers?’ I said Buddy Rich and Billy Cobham, giving all the wrong answers.”11

“Look Here” doesn’t take a sledgehammer to its source material like many Clash covers, but it certainly adds some juice. Headon’s drums in particular do way more than those on the original. Jones’ vocals are woozily multi-tracked. Mickey Gallagher lets himself go a little crazy on the keys. The tempo is up, adding some urgency to the Clash-like message of waking up and making the most of the moment. Still, even with the extra chug, “Look Here” probably could have better execution. I think all the playing is great, but the it could have gone a long way for the production to give it more muscle. And the vocal production probably works against the recording, making it sound less than confident, like a tacit acknowledgment that this is not Sandinista!‘s A-material.

The Stragglers

We’re finally getting into more legitimate territory here, but we’re not quite free. Before we get to the three wholly original Clash songs at #23-21, let’s take inventory of the contents of #36-24:

•3 dub tracks based on Clash original songs from Sandinista!

•1 dub track based on a cover song from Sandinista!

•1 dub track based on a cover song from a prior album

•1 remake of a Clash original song from a prior album

•1 dubbed reversal of a Clash original song from Sandinista!

•2 cover songs

•1 Clash original song stapled to a dub version of itself

•3 wholly original Clash songs

Golly. From #23 and on, it’s 22 wholly original Clash songs (one of which is actually a Clash original song stapled to a remake of a Clash original song from a prior album) and just one cover. We’re just about home free.

25. “Midnight Log”

mean: 21.8

33⅓: 0

Sandinista!‘s fourth side is just about its strongest, but something has to be the loser, and it’s “Midnight Log.” “Midnight Log” actually musters up a pretty fun rockabilly shuffle and has a pretty spiffy backing track in general, but I think Strummer’s vocal patterns make it sound like a throwaway. I’m not sure how many voters were scouring lyric sheets by track 20, but while they have a sort of Bob Dylan circa 1965 quality to them, that comparison just betrays that they’re not much. Evildoers are about, but the devil will collect the taxes they owe (Henley ventures that the title might refer to “the devil keeping track of his debtors”12). It’s hard to muster up a ton to say about “Midnight Log.” It doesn’t have anything too interesting bogging it down. Most voters just recognize it as a bit of a standard whiff. It happens.

24. “Junco Partner”

mean: 21.6

33⅓: 1

“Junco Partner” is a pretty quiet 24th place, though in 33⅓, Randal Doane selects it to his personal twelve track version of the album. Indeed, it was included in the original Sandinista Now! edition. Written by Bob Shad and first recorded by James Waynes in 1951, The Clash were actually inspired by James Booker’s 1976 recording of the song and in fact erroneously credited him as the writer when Sandinista! first released.

You can actually listen to a live recording of the song Strummer did with his pre-Clash band The 101ers.

Mikey Dread’s mitts are all over “Junco Partner” before it even could become “Version Pardner” with all its weird electronic sounds. This is also the only song The Clash got to record on their trip to Kingston for this album (more on that trip in a second), and for their efforts, they got to use the piano at the legendary Channel One Studios for the skank.

The problem with “Junco Partner” is that it’s too long. A number of Sandinista! tracks break five minutes, but the others are either more beloved, more substantial, or are tracks that repeat twice for no reason (see #29). Strummer actually puts in a great performance, probably one of his best on the album, but it’s just too long and too weird, especially next to the great songs on Sandinista!‘s awesome first side. Only twelve tracks were included on Sandinista Now!, and unfortunately “Junco Partner” did not earn its way in.

Notably, “Junco Partner” is the lowest-scoring song to appear on the promotional Sandinista Now! LP, though all five of the first tracks do.

23. “Kingston Advice”

mean: 20.8

33⅓: 0

All right. We are now really getting into it. I actually put “Kingston Advice” all the way up at #12. It’s the highest I ranked anything relative to this overall rank. The people generally did not agree, although the song has the seventh highest standard deviation. The middle fifty percent spans #13.5 to #28. So what’s the deal?

After their debut, Strummer and Jones took a two week trip to Kingston to write for their second album, what would become Give ‘Em Enough Rope. But instead of enjoying their trip to the home of so much music they loved, they were scared shitless and spent most of the trip in their hotel room. They immortalize their experience in “Safe European Home,” one of the very best Clash songs. “Sitting here in my safe European home/I don’t want to go back there again.”

And yet back there again they did go. Simonon recalls: “At one point we went to Kingston, Jamaica, which was great, ‘cos I was there at least. I spent the whole time with Mikey and he’d introduce me around to guys. One day he says, ‘You gotta check this bloke out, he’s been shot 18 times.’ I noticed he had a pistol tucked in his sock. Afterwards Mikey says, ‘He’s famous ‘cos he caught these guys robbing a bank and made them crawl all the way to the prison from the bank.’ Mikey was my passport out there. If I’d been on my own I’d have been at the mercy of Dodge City. I mean, that’s what Kingston was like, Dodge City.”13

Strummer remembers: “When we were in Jamaica recording ‘Junco Partner’ with Mikey Dread there were gunfights going off all around us in Trenchtown. There was a political rally taking place and we went in like complete idiots, without knowing that we had to buy off the godfather to be allowed in.” Then, when they started recording this song: “I was sitting at the piano in Studio One, which has that lovely out of tune sound which is the sound of the town, when Mikey tapped me on the shoulder and I said, ‘What?’ and he says, ‘We have to run’ and I looked into his eyes and realized that he was completely serious.”14

As it turned out, The Rolling Stones had recently recorded some of Emotional Rescue at Channel One and had given out a ton of money so that they wouldn’t be bothered. When The Clash, far from similarly wealthy, weren’t as generous, some locals didn’t take particularly kindly to that.

While it takes “Safe European Home” to really get into Strummer’s mindset on “Kingston Advice,” it’s not really a sequel. The Clash are taken out of the story and the song is simply about people suffering and a country at war. I’ll defend “Safe European Home” until I die, but its foregrounding of a terrified white experience in Jamaica might make some wince. “Kingston Advice” does not have the same baggage.

So what gives? Musically, “Kingston Advice” is actually pretty awesome. That chorus is huge, one of their showiest on the album. Well, first off, I think the three real actual songs after “Junkie Slip” might suffer from a sequencing bias. I think some folks quite reasonably feel like the band is out of gas at that point. However, “Kingston Advice” also suffers from some pretty baffling production choices. Joe’s vocal on the verses is buried underground, struggling to get through. Weird beep boops echo to open the song. But I still think that chorus absolutely shines, and “Kingston Advice” would sneak onto my personal twelve track version of the album.

22. “The Equaliser”

mean: 20.8

33⅓: 2

“The Equaliser” was yet another track that had people all over the place. Its middle fifty percent spans 15th to 28th, and quite a few people had it in their top ten. In 33⅓, Zeth Lundy and Randal Doane included it in their lists. Author Micajah Henley greatly admires it. On the other hand, Keith Topping, author of The Complete Clash, seems to completely despise it. A lot of people shrugged at “The Equaliser,” myself included (I had it down at #28), but some people went seriously to bat for it.

I think “The Equaliser” is a great example of Sandinista!‘s production neutering a fine song. Though Henley notes that the song is a great example of The Clash finding their groove in a style of reggae all their own, I must once again stand up for The Clash’s need for some kind of oomph, and just the bass is simply not enough. The production of Strummer’s vocals here is a tragedy. That said, while this track is too slow and muddy to stir much within me, there are good things happening. The piano tracks the off-beat so lightly that the reggae aspect can sneak up on you. Tymon Dogg’s violin is just excellent here, and it pairing with a dark, urgent song reminds me of some of The Mekons’ Clash-indebted 1985 masterpiece, Fear and Whiskey.

Maybe that’s why this song has so many champions. But in the end, Strummer’s lyrics don’t do enough to overcome this plodding song, Sandinista!‘s very longest (unless you count the coda of our #20) at 5:47.

21. “If Music Could Talk”

mean: 20.5

33⅓: 0

“If Music Could Talk” is a wandering jam, and while it’s almost certainly more pleasing to the ear than the later dub tracks, there’s still not a ton to latch on to. Musically, session saxophonist Gary Barnacle absolutely carries the track. Meanwhile, Strummer, in a move that feels more like something you’d find on Combat Rock, has separate vocal tracks in both the left and right channels, having an argument with himself while he waits for musical hero Bo Diddley to finish an opening set for them. It actually makes for a pretty fascinating and compelling lyric sheet, but the vocals are so far back that it’s hard to appreciate. “If Music Could Talk” is, after all, about the music. Joe lets it do the real talking.

The Edge Cases

You’ve officially made it to the fun part. Everything from this tier and on is pretty damn good. These five songs likely won’t pop into mind the second someone thinks about Sandinista!, but they’re key to how deep the album is. Yeah, there’s a bit you can lop off, but Sandinista! has twenty songs that could make up an awesome double LP.

20. “Broadway”

mean: 19.7

33⅓: 2

“Broadway” rocks the third highest standard deviation of any song here. Makes sense. You could hear “Broadway” as either grand or just slow.

Per Clash roadie Barry Glare in the Clash On Broadway booklet, “We stayed at the Iroquois Hotel. Outside was a heating vent. There was always this one particular bloke, standing or sleeping on it. I remember one night we came back from the studio about four in the morning and Joe was looking at this guy quite intently. I always thought ‘Broadway’ was about him.”15

“Broadway” is especially satisfying in the context of the album. “Something About England” is about an encounter with a British street tramp with a very British music hall sound, while “Broadway” is about an encounter with an American street tramp with a very American jazz sound. In each song, the tramps begin to tell their life story when approached, and in doing so say so much about the recent history of their country. We will get to “Something About England” much later, but while the old man from that song is eager to enlighten our protagonist, any education in “Broadway” is incidental. This guy is tripping over himself to give us his life story, and he’s not telling it particularly well. He was born during the Depression. He was a boxer, and it seems unlikely he was all that successful. He’s hungry. And then he locks in on a dream: one of those cars. Perhaps he wants to escape it all. Perhaps it’s a simple, materialist fantasy. Strummer inhabits the character so well, and Gallagher’s climbing keys render “Broadway” an unequivocal success.

To me, “Broadway” always felt like the true showstopper finale of the album, sliding in right after the climax of “Washington Bullets,” with the final Sandinista! LP just a happy bonus. It’s the album’s “A Day In The Life,” its “Fillmore Jive.” I mean, it’s not as good as those, but you get me.

Then Gallagher’s then-four-year-old daughter Marcia shows up to sing “The Guns Of Brixton,” in much the same way his older boys sang “Career Opportunities.” She knew the song because she was, as her father claims, “besotted by Paul.”16

19. “The Street Parade”

mean: 19.4

33⅓: 2

“The Street Parade” is a great test to see whether you’re still paying attention by track 30. Like “Kingston Advice,” it sounds almost underwater, so I imagine some listeners might not be clued into the fact that they’re listening to something quite worthwhile. The thing is, though, with “The Street Parade,” I think the sound ultimately works. The echo might still be wrong for the vocal, but it does wonders for the guitar and the saxophone.

Many of Sandinista!‘s lyrics find Strummer troubled and searching, but his lyric sheet for “The Street Parade” sounds devastated. After a brief window into his sadness, he defiantly insists “I will never fade,” though at the same time he will “disappear into the street parade.” In the final refrain, he merges two ideas that he previously framed contradictorily and says that, in fact, he’ll fade into the street parade.” One might read that Strummer intended a retreat from public life, though that never really came about even after the demise of his most famous project. After Strummer’s death by heart attack in 2002, the song took on greater significance, as it’s the one in the band’s catalogue that speaks the most to the tragedy. Joe Strummer was just fifty years old.

“The Street Parade” might just be the band’s most hidden gem in plain sight. They certainly thought so, slotting it as the hidden track on their 1991 box set Clash On Broadway.

18. “Ivan Meets G.I. Joe”

mean: 18.8

33⅓: 1

Though the people were pretty divided on “Ivan Meets G.I. Joe” (eighth highest standard deviation), I think it’s pretty clear that the song rules. The USA and the USSR try to settle things through a dance-off, and all the moves are world destruction. Ivan does the Vostok bomb, the radiation, the chemical plague. G.I. Joe simply “wiped the Earth clean as a plate.”

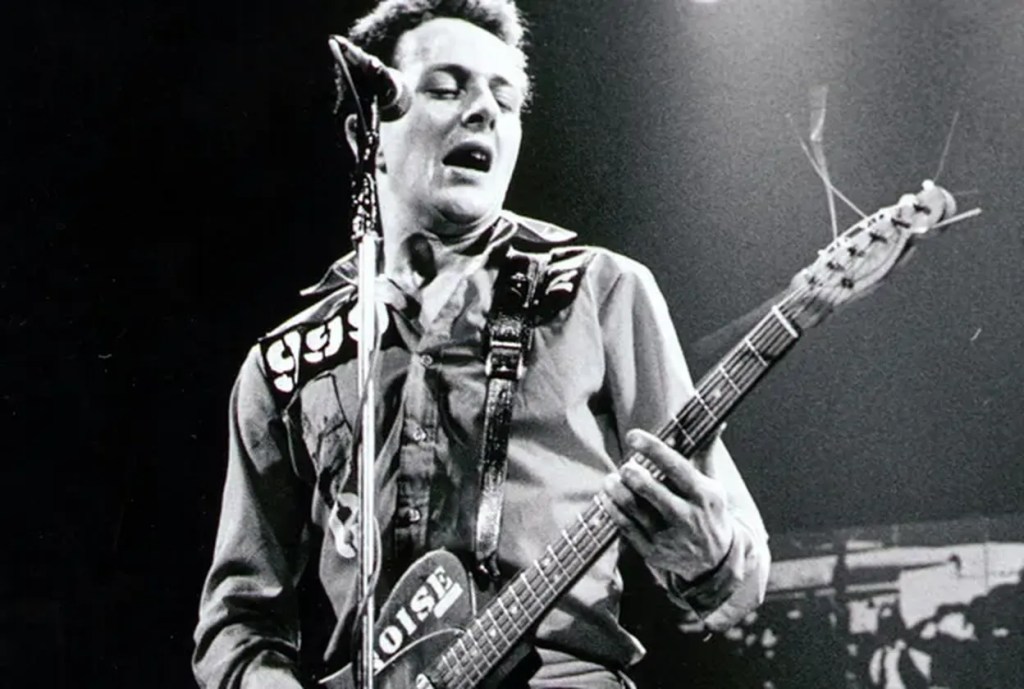

Headon’s big moment with The Clash was “Rock The Casbah,” with him writing and recording most of the music and instruments on the band’s biggest US hit (Headon would tragically be fired before the band recorded the music video, deeply upsetting him when he saw someone else drumming in the video to his song). But his next biggest is “Ivan Beats G.I. Joe” (Headon wrote all the music, Strummer wrote the lyrics), which is absolutely no “Rock The Casbah,” but the two share a sort of kinship in their wartime imagery meeting stories about joyously dancing and rocking out. Here, Headon takes his only-ever turn on lead vocals, and I think he does just fine. Henley observes that Headon sounds like he’s a commentator giving us the play-by-play. Moreover, the horns evoke flashing lights going off at the venue of a big marquee boxing match. The music is a flashy chaos fitting of the battle everyone is literally dying to watch, in which everyone literally dies.

Strummer’s lyrics focusing on a dance-off is one of many appearances of the band’s obsession with early hip hop culture throughout Sandinista!, and we will talk more about that much later.

“Ivan Meets G.I. Joe” was included on the promotional Sandinista Now! LP.

17. “Let’s Go Crazy”

mean: 18.5

33⅓: 3

The top fifteen songs here are pretty significant, as the mean gap between #16 and #15 is pretty large. However, “Let’s Go Crazy” and its sister song (see #16) are the lone songs that could be argued as perhaps being deserving. The median ranks for “Let’s Go Crazy” and our #16 song each beat that of our #14 song.

Indeed, “Let’s Go Crazy” would be a heartbreaking cut. It’s one of The Clash’s most impressive genre exercises, a Carribean soca inspired by Strummer’s attendance of the Notting Hill Carnival, the humongous Caribbean Carnival celebration that takes place in Kensington each year (“the second largest Afro-Caribbean celebration in the world”17). The intro and outro of “Let’s Go Crazy” feature Ansell Collins calling for peace and love at the Carnival. Collins actually topped the UK charts in 1970 with “Double Barrel” as part of duo Dave & Ansell Collins, and he actually played on the original Maytals “Pressure Drop” that The Clash covered in 1978.

Notting Hill had actually been the site of the riot that inspired the band’s first single, “White Riot.”

“Let’s Go Crazy” has one of Strummer’s sharper lyric sheets, too, the highlight probably being “Owed by a year of S.U.S. and suspect/Indiscriminate use of the power of arrest,” S.U.S. (often just “sus”) laws essentially being British stop and frisk laws18 that got Joe a light fine for weed possession.19 But though it carries the darkness of contemporary events, “Let’s Go Crazy” is The Clash’s most joyful anthem of liberation. Its characters are “smoking to the Mighty Sparrow’s blast” – nodding to the calypso legend – while one “drums away 400 years of dread,” a nod to Bob Marley & The Wailers’ “400 Years,” itself a nod to the Rastafarian belief of a long period of slavery and exile that mirrors the Israelites’ 400 years in Genesis.20

“But you better be careful,” the band still warns. “You still got to watch, watch yourself!” Don’t get too crazy.

16. “Corner Soul”

mean: 18.2

33⅓: 2

Like “Let’s Go Crazy,” “Corner Soul” does make a dent in our top fifteen, with its median rank scoring higher than our #14 song. Again, it’s easy to hear why. “Corner Soul” is one of the simplest pleasures on Sandinista!, a beautiful soul song with one of the album’s hugest choruses, sounding like Strummer is booming from the mountaintop. Ellen Foley, who we will cover in more detail in good time, provides a perfect supporting vocal. Strummer’s words strike a perfect balance of clarity and urgency.

He’s being facetious on the chorus when he asks “is the music calling for the river of blood?” Enoch Powell’s 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech (“As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood'”), in which he warned of the dangers of immigration, remains a seismic moment for the British right, and such sentiments remain mainstream, even prevailing, both in the US and the UK. The music of Grove Skin Rock is that of the Notting Hill Carnival, which passed through Ladbroke Grove. In fact, “Corner Soul” is indebted to Max Romeo & The Upsetters’ “War Ina Babylon,” another song that describes growing cultural tension on the street. It’s sipple out there!

“Corner Soul” is all about these simmering tensions, communicating the darkness of the situation with the signature Clash empathy. Actually, riots stemming from a cocktail of police violence, racial oppression, and right-wing, anti-immigrant politics dominated England in the 1980s. “Corner Soul” was recorded after 1980’s St Pauls riot, and the song would continue to remain prescient during more widespread riots in 1981, 1985, and on.

Considering it’s about the Notting Hill Carnival, a fitting answer to “Corner Soul”‘s hypothetical is “Let’s Go Crazy.” It’s fitting, then, that not only does the song follow it on Sandinista!, but the two songs are ranked right next to each other here. I would never dream of separating them.

The Second Tier

While these aren’t the most celebrated songs on Sandinista!, plenty turn up as occasional favorites, and a few are just reasonably beloved by all. I’m not so sure the previous tier’s songs are definitely better than this tier’s, but our process has determined that these are more in favor.

15. “The Sound Of Sinners”

mean: 16.7

33⅓: 3

I would call “The Sound Of Sinners” the most controversial song on Sandinista!, per these results. Only “Career Opportunities” had a higher standard deviation, and that was more a matter of people not knowing what to do with it. This song’s middle fifty percent of rankings spans as high as #8.5 but as low as #23. It is the only song with both a #1 vote and a #36 vote. This was a bit surprising to me. “The Sound Of Sinners” has a lot of respect! It’s Elvis Costello’s favorite Clash song, period (I can’t find the original source for this, I tried, but everyone repeats it, so it’s probably true).

I think that some voters are revenant of what might be The Clash’s boldest genre experiment (well, maybe excepting the dubs) while others find the sound grating and can’t take the repetition. I do have to imagine “The Sound Of Sinners” sets a record the Clash chorus that repeats the most.

“I was thinking of LA and the great earthquake. I had, ‘After all these years to believe in Jesus.’ Topper said, ‘How about drugs?’ All those people who take too much LSD and end up in sanatoriums. Lots of them think they’re Jesus.”21 Strummer writes from the perspective of a drug addict, and his indulgence in Bible references brings out some of his most striking lyrics. “I was looking for that great jazz note.” “The winds of fear whip away the sickness.” That whole second verse. “The Sound Of Sinners” used to be my favorite Sandinista! song, and I still had it #8 on my ballot, one of my largest deviations from this final ranking. It sounds a little more awkward to me now, but I love how daring it is, that it’s simultaneously reverent and irreverent, and of course its lyric sheet. My dad got Sandinista! in a double MiniDisc set, and “The Sound Of Sinners” was probably his favorite.

On a related note, the band considered titling this album The Bible, likely as a reference to just how much was here. It would have been interesting for the title to nod to the importance “The Sound Of Sinners” rather than “Washington Bullets,” a song we will get in a while.

The preacher at the end of the track is played by Den Hegarty of Darts.

“The Sound Of Sinners” is included on the promotional Sandinista Now! LP.

14. “The Leader”

mean: 16.5

33⅓: 3

Pretty much across the board, people thought “The Leader” was one of the better songs on Sandinista!, but not the best. Such is the way with comedy, not just in film but in music. “The Leader” is a recounting of the Profumo affair, a scandal that rocked British politics in the 1960s so thoroughly that the Prime Minister resigned and the Tories lost power the next year. If you’ve ever wondered what Billy Joel was referring to with the “British politician sex” line in “We Didn’t Start The Fire,” it’s this.

“The Leader” chugs along as a rollicking rockabilly, almost with a surf rock feel, and details a delightfully infamous moment in Tory history. MI5 had a relationship with shifty osteopath Stephen Ward (I will refrain from talking at all about Ward, as we could be here all day), and they saw Captain Yevgeny Ivanov of the Soviet Embassy in London as a potential defector. They requested Ward’s assistance in the matter, and wanted to use the young model he lived with, Christine Keeler, as a honey trap. Keeler did end up having relations with Ivanov, but she also had relations with Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s war minister John Profumo. The Profumo affair eventually became public, and the political fallout, due to both the potential compromise in intelligence and the simple untowardness of it all, was considerable. Ivanov was recalled by the USSR. Profumo resigned after he admitted he had lied to the House when denying the affair. Macmillan resigned some months later, supposedly due to health. Ward overdosed on sleeping pills near the end of his trial. Christine Keeler kept living, but it sounds like it wasn’t great.

But there was a reason this story captured the public imagination to the extent it did. Keeler met Ivanov and Profumo at sex parties attended by the British elite. There was a rumor that a naked masked man would attend, and his identity might have been a cabinet minister or a Royal Family member. It was rumored that he would be whipped by attendees.22 The nature of the rumors fueled much of the public interest in the scandal. The people must have something good to read on a Sunday.

“The Leader” probably gets its humorous edge from the fact it engages at all in palace intrigue. Clash songs seldom speak very concretely about the elite and the political leaders, so, perhaps by necessity, when they do, it’s to dress them down. A few lines live in my head forever. Of course, there’s “The leader never leaves the door ajar/Swings a whip from the Boer War,” Strummer very pleasingly pronouncing it “boh-war-war.” But the best is the way Joe phrases that “The leader let the fat man touch her” (the fat man being Ivanov and the thin man later in the verse being Profumo).

“The Leader” is a simple pleasure, and at 1:42 it’s the shortest song on the album by almost a half-minute. It also appears on the promotional Sandinista Now! LP. Amy Rigby has a great cover of “The Leader” on 2007’s The Sandinista! Project: A Tribute To The Clash.

13. “Rebel Waltz”

mean: 16.3

33⅓: 4

“Rebel Waltz” is another song squarely in the liked-not-loved category, but notably it’s the first song with a 33⅓ score of 4. If we were to make a top twelve from those scores alone, “Rebel Waltz” would be the eleventh track added (the last could be any of four songs with a score of 3, including “Let’s Go Crazy,” “The Sound Of Sinners,” “The Leader,” and our #11 song below).

Possibly excepting “Straight To Hell,” no Clash song is as quietly gorgeous as “Rebel Waltz.” After an extended intro of interplaying guitar and harpsichord (the song is indeed a ¾ time waltz), Strummer finally gets his first word out at a minute seventeen. It’s no surprise that “Rebel Waltz” is one of Strummer’s most abstract and poetic songs considering he introduces it as a dream. The army of rebels is merry, they’re plunged into conflict, they’re defeated, and they rise once more. Strummer gives us a bit more to cling to throughout: “I danced with a girl to the tune of a waltz,” “In a glade, through the threes, I saw my only one,” “A child cried for food.” I quite enjoy “Rebel Waltz,” though I have it down at #19. It being #13 makes sense and is fine, but I roundly prefer the second tier Sandinista! songs that have a bit more energy.

“Rebel Waltz” is based on an actual dream Strummer had23, so even the nature of the war itself seems uncertain. The Spanish Civil War and various Irish rebellions feel the most fitting. He likely didn’t have anything specific in mind when he sang that “the song was an old rebel one,” but early 19th century Irish rebel song “The Minstrel Boy” seems to fit the bill. Shockingly enough, Joe Strummer & The Mescaleros released a cover of the song in 2001. It’s not very good, but get this: they did it for the Black Hawk Down soundtrack, a choice so incongruous that I have to hold myself off from unpacking it.

“Rebel Waltz,” which also credits Simonon as a cowriter, is the only original song in The Clash’s catalogue to credit Strummer as a writer but not Jones.

12. “Lightning Strikes (Not Once But Twice)”

mean: 15.7

33⅓: 2

A wishful title. We will get to “The Magnificent Seven” later, but the title “Lightning Strikes (Not Once But Twice)” seems like a nod to this being that other hip hop song on the album. So does it get the job done?

Musically, I think so. Whereas “The Magnificent Seven” sounds so smooth and controlled, “Lightning Strikes” is closer to a rock song, louder and much more chaotic. The main riff makes the song sound like it’s in perpetual imbalance. Headon’s drums give the thing bounce and power. Strummer shouts clearly and freely on the refrain. “Lightning Strikes” is a really fun time.

It’s a shame then that the lyrics are pretty thin. “Lightning Strikes” is basically Strummer’s travel diary from their time in New York City while stationed at Electric Lady. And there just aren’t a lot of lyrics that are worth much here. “See New York’s one and only tree” is nifty. I like “Graffiti Jack sprays in black/An Englishman, can he read it back?” because it evokes the band’s obsession with the burgeoning hip hop culture in the city. While Mick was obsessed with the music, Joe was interested in the aesthetic pillar of hip hop: graffiti. So this couplet makes you picture Joe wandering the streets appreciating graffiti, squinting and trying to make out the letters.

More often, it’s amateur hour. “If this is spring then it’s time to sing/Never mind the little birdie’s wing.” “It’s Cuban Day, oy vey!/Chinese New Year let’s call it a day!” It sounds like Strummer is enjoying himself, but what are we doing here?

Later on, Strummer twice addresses a “Chi man,” and though it’s not certain what he’s on about, it might, as Henley puts it, “a racial moment.”24 Regarding “A Polaroid, caught in the act/You’re married too, and that’s a fact/But I won’t peek, and I won’t squeak/Down by the trucks on Christopher Street,” Henley writes: “Again, there’s no mention of the Stonewall riots and the gay liberation movement that it spawned. Strummer is more concerned with spotting a married man in a part of the city known for its queer culture in the act of a homosexual affair.”25

“Lightning Strikes” is the one song on this album that had me liking it less the more I researched and read about it. I had it down at #21 on my ballot, but I get that it’s a blast musically, so it’s no surprise that its final rank is much higher.

The intro is a recording from WBAI, a storied and independent radio station in New York City. The voice is that of Labbrish host Habte Selassie, who had started at WBAI the year prior and who continued hosting Labbrish for forty years until the station finally shuttered in 2019.

11. “One More Time”

mean: 14.4

33⅓: 3

Though it’s not melodically flashy, “One More Time” is by far the most successful track on the album that involves Mikey Dread co-producing. It’s a known highlight of the album, and it’s no surprise that it waltzes to a solid eleventh place here.

“One More Time” is not really about the lyrics, which aim to evoke more than tell any story. The old lady kicks karate. The little baby knows kung fu. Strummer refers to silicon as “silicone” again. He references the Watts riots and the Montgomery bus boycott. It’s not clear what is being given one more time. Perhaps one more attempt at changing the world through the power of a riot? Or is this the last time in the slums before people can’t take deteriorating conditions anymore?

Though the message isn’t crystal clear, the performance is. The charm of “One More Time” is its relentless intensity. Strummer jumps in growling that Marvin Gaye song title. Dread shouts “hey!” like a crying bird. Gallagher’s piano stabs color in the song with a nervous darkness. Headon’s drums are anxious. Watt-Roy’s thick bass lines carry the whole thing. “One More Time” is probably the least complicated great song on the album. I have it a bit lower at #17, preferring the more melodic second tier tracks, but “One More Time” just works.

10. “Lose This Skin”

mean: 13.7

33⅓: 5

“And did you say you were in the mood for a stomach-churningly terrible country-fiddle hoedown? Brace yourself for ‘Lose This Skin,'” Rob Sheffield warns on his 40th anniversary retrospective of the album, “the fugliest dud on an album that flaunts its duds with pride.”26 It’s true that “Lose This Skin” is controversial (it has the fourth highest standard deviation), but Sheffield is largely overruled not just here but in 33⅓. There, “Lose This Skin” is one of only ten songs included on at least five of the nine lists at the end of the book. Here, the song is similarly a rather solid tenth place. “Lose This Skin” is one of only ten songs here to get at least one first place vote. Folks tend to think “Lose This Skin” rules. But who is that man singing?

In 1970, Strummer began university at London’s Central School of Art, where he would eventually drop out. While there, he would become housemates with one Tymon Dogg, who was already an established musician. Dogg signed to Pye Records (then performing as “Timon”) at just seventeen years old and eventually was part of Apple Records. Before meeting Strummer, Dogg toured with The Moody Blues and had recorded songs featuring playing by Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones, James Taylor, and Paul McCartney (I don’t think Dogg’s early stuff is worth seeking out, but the instrumentals sound really good). Just three years after he signed his first record deal, he was busking around London with his violin.

Strummer learned how to perform while accompanying Dogg’s busking in the early ’70s. “I ended up bottling for this busker, and it was like, I found out later on, the apprenticeship of a blues musician. I got a real kick out of that. All the great blues players started out collecting the money for some master, to learn the licks. The guy I bottled for would play the violin and eventually whenever there was a guitar lying around from another busker I would borrow it and he would teach me how to accompany. Just simple country and western and Chuck Berry.” 27

Now a decade since they met, Dogg happened to be in New York City at the same time that The Clash were recording at Electric Lady, and by complete chance Dogg encountered Mick Jones. The band found themselves backing up Dogg on his new song, which was also eventually released as its own single (for Dogg, not The Clash). Dogg remembers: “The Clash worked on that track for days of their own recording time. There was a real openness and generosity of spirit at that time.” “It felt like they got this facility now and they really wanted to share it. They didn’t have to do that.”28

“Lose This Skin” is significantly more jagged and interesting than anything he’d recorded before he met Strummer. The multitracked violin is ferocious, and obviously Dogg’s vocal conviction goes a long way to sell the song. “Do not turn or hate to see/What happened to the wife of Lot” is a good lyric on its own, but Dogg is gasping and losing control by the verse’s end, and his transition to the refrain gives his delivery of “the wife of Lot” just so much character. If Dogg’s vocal approach doesn’t immediately repel you, it will absolutely win you over. “Lose This Skin” is a song about breaking free and finding your place, and Dogg’s vocal sounds like it’s coming from someone genuinely engaged in that escape and discovery.

I do think the band provides an important sonic base for Dogg here. His subsequent 1982 album, Battle Of Wills, is just him and his violin, and it’s significantly less engaging. I don’t particularly recommend further investigation on that front, unfortunately. There is only one “Lose This Skin.”

“Lose This Skin” deceives us. After quasi-finale “Broadway,” it opens up the third LP as if to tell us that the band is not out of gas yet. It’s not exactly true, but it’s certainly convincing. It’s one of the strongest vocal performances on the album, and, I think, easily the most successful of the three guest vocal songs, though we have the third coming up shortly.

Apart from “Lose This Skin,” Dogg plays violin throughout Sandinista!, and he would go on to play piano on Combat Rock finale “Death Is A Star.” Many years, later, Dogg would make many musical contributions to 2001’s Global A-Go-Go, Strummer’s final album released before his death in 2002.

The Top Tier

Though there are five even higher, these four songs are squarely in the top echelon of Sandinista! tunes. There’s really no way around it. Represented are two of the album’s three singles, one of the band’s most ambitious moments, and a third LP track that, somehow, nobody failed to notice. There is a whole lot of of Mick Jones this high in the list. Though he never outright leads on these four songs, he has significant vocal contributions on every track.

9. “Charlie Don’t Surf”

mean: 12.6

33⅓: 9

“Charlie Don’t Surf” is set up for a fall. It’s on the third LP. Its intro is a bunch of strange synthesizer noises. But it turns out that people haven’t quite tuned out by track 32. “Charlie Don’t Surf” fared great on this poll. It’s the clear #9, and is in fact considerably closer to #8 than to #10. It’s the only song outside of the top five to receive multiple first place votes. It’s one of only three songs to appear on every single Sandinista Now! at the end of Henley’s 33⅓. “Charlie Don’t Surf” is often thought to be a bit of a secret highlight in The Clash’s catalogue. Seems like the secret’s out.

“It doesn’t leave you,” Strummer once said of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 film Apocalypse Now (in fact, the promotional LP Sandinista Now!‘s title is a reference to the film). “It’s like a dream.”29 Nowadays, Apocalypse Now has a strong reputation as an epic war movie, one of the greatest films of all time. It sits at #19 on the most recent Sight And Sound poll of the greatest films of all time, and a couple of quotes in particular endured. The big one is “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.”

The other isn’t quite as household, though it serves a similar purpose. Robert Duvall’s Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore – in asserting that his men needed a beach they’d just taken and the Viet Cong (codename Charlie) did not – simply deadpans, “Charlie don’t surf.” Like the napalm line, also spoken by Kilgore, it demonstrates a disturbingly callous perspective on the horrors of war.

This line, from co-writer by John Milius, was actually inspired by Ariel Sharon. When the then-General and future Prime Minister of Israel captured territory during 1967’s Six-Day War, he went skin-diving and said, “We’re eating their fish.”30 Gotta say, taking a sentiment spoken by Ariel Sharon and giving it to Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore? A lot going on there.

Anyhow. It’s not enough to get your title from a classic film line. After the weird synth sounds, “Charlie Don’t Surf” snaps into place with some of the band’s finest pop sense. It’s hard to tell for sure, but I think Strummer and Jones sing every line together, with Jones’ more melodic approach and Strummer’s rougher emphasis occasionally poking ahead of the other. And the approach is awesome, giving the lyrics some bite while also serving the central melody well. Maybe the title is biasing me, but “Charlie Don’t Surf” seems about the most Beach Boys The Clash ever got outside of “1-2 Crush On You.” The song is so musically successful that people seem totally fine that it ends with a breakdown that’s over two minutes long.

On “Charlie Don’t Surf,” The Clash do Kilgore one better. Maybe he should surf. The more American thing would be to impose American values on Charlie. After all, “Africa is choking on their Coca-Cola” (in a bizarre twist of fate, it seems likely the writing of that line precedes the release of 1980 comedy classic The Gods Must Be Crazy by a matter of months).

On one verse, Strummer and Jones play xenophobic Westerners: “We’ve been told to keep the strangers out!” On the next, they’re candidly appraising the modern usefulness of imperialism: “The war of super powers must be over/So many armies can’t free the earth.”

“Charlie Don’t Surf” is a Clash song that’s both melodically great and globally political aware, a perfect balance for a Sandinista! track. Only one song here does all of that better. We will get to it later.

Strummer once remembered seeing Tear For Fears’ Roland Orzabal in a restaurant and telling him, “you owe me a fiver.” “He asked why. I said, ‘”Everybody Wants To Rule The World” – “Charlie Don’t Surf” – middle eight, first line.’ He reached into his pocket, got out five and gave it to me.”31

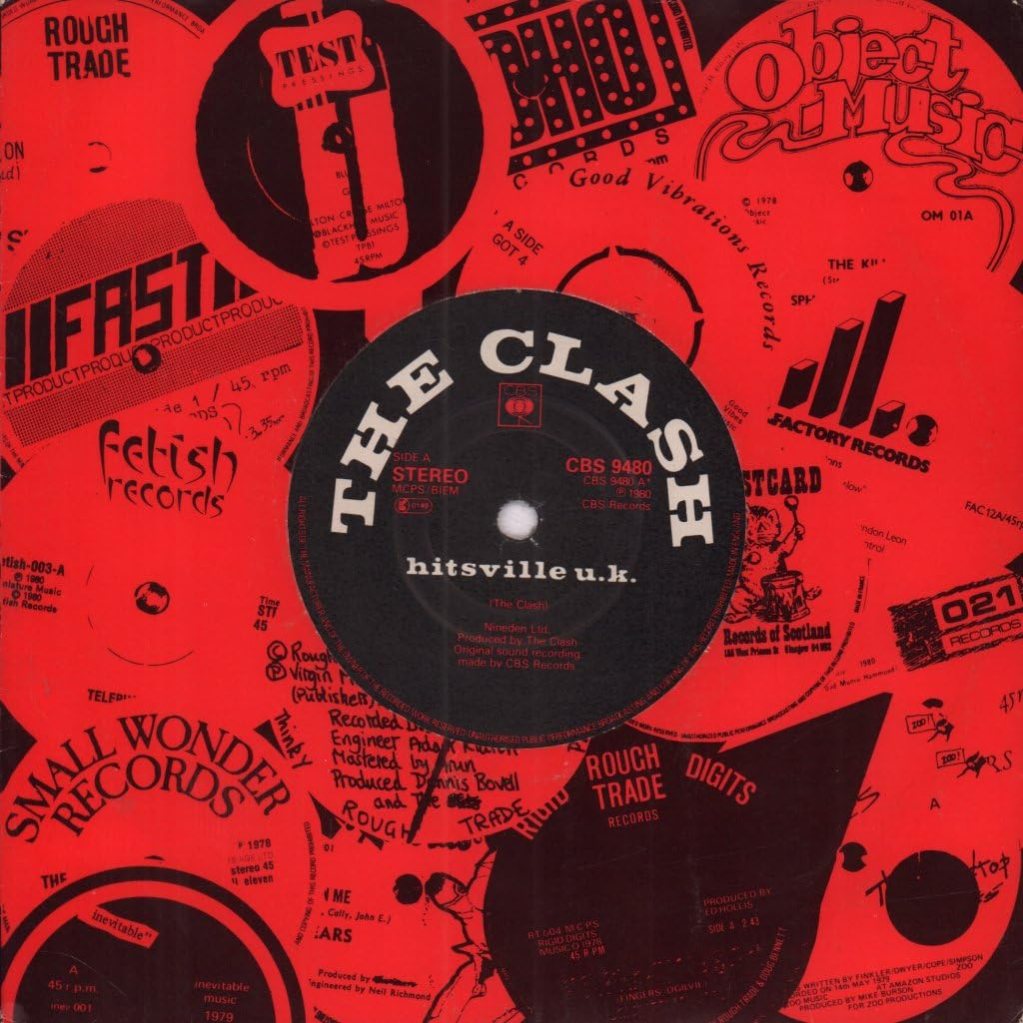

8. “Hitsville U.K.”

mean: 12.1

33⅓: 6

Though “Hitsville U.K.” has solidly made the cut, the album’s second single only making it to #8 might be a bit of an underperformance. Though the upside of its middle 50% of votes was #6, the downside was #18.5. I myself had it at #18. The song had the sixth highest standard deviation. How could such an innocent, cute song be so controversial?

“Hitsville U.K.” posed that the British indie labels were having a moment reminiscent of sixties Motown, nicknamed “Hitsville U.S.A.” The Clash celebrated this despite being on CBS themselves, name-checking Small Wonder, Fast Product, Rough Trade, and Factory Records (“When lightning hits Small Wonder/It’s Fast Rough Factory Trade”). The song is wildly optimistic about this moment. How does this optimism look today?

Fast Product was best known for singles like Gang Of Four’s “Damaged Goods,” The Human League’s “Being Boiled,” and The Mekons’ “Never Been In A Riot” (an answer to The Clash’s “White Riot,” actually). Fast Product stopped releasing new music around 1981.

Small Wonder was best known for singles like The Cure’s “Killing An Arab” and Bauhaus’ gothic rock Big Bang “Bela Lugosi’s Dead.” Small Wonder stopped releasing new music around 1983.

Factory Records was best known for Joy Division’s releases, with lead singer Ian Curtis committing suicide during the months Sandinista! was being written and assembled. The surviving members formed New Order and helped keep Factory Records going. Eventually, the band reunited to record “Regret,” one of their finest songs, to save the label, but it went bankrupt in 1992 before the song was released the next year. Though it did fold eventually, I would still say that Factory Records was an enduring success in a way Fast Product and Small Wonder weren’t, despite mostly being kept afloat by the loyalty of New Order.

Rough Trade was getting to be a post-punk powerhouse, already having released Young Marble Giants’ Colossal Youth, The Raincoats’s debut album, Stiff Little Fingers’ Inflammable Material, Cabaret Voltaire’s Mix-Up, and a few Kleenex singles. Actually, in 1980, the label released a fantastic compilation album called Wanna Buy A Bridge? celebrating the label’s output. It’s very worth your time. Rough Trade would go on to be major champions of British indie, releasing major works by The Smiths, Aztec Camera, and The Libertines. Rough Trade is still going strong, with some recent releases including recent albums by Geordie Greep, Amyl And The Sniffers, and Lankum.

Other labels like Postcard Records (folded in 1981), Object Music (folded in 1981), Good Vibrations (folded in 1982), Step-Forward Records (folded in 1983), 2 Tone Records (folded in 1986), Fetish Records (folded in 1986), and Stiff Records (sold to ZTT in 1987), though not name-checked in “Hitsville U.K.,” were almost certainly part of what the song was celebrating.

Though British indie itself would continue to gain traction, the utopian ideal The Clash were heralding would backslide as, by and large, the bands that made these labels relevant moved to labels with more money and better distribution. I doubt The Clash felt like they had egg on their face, but it’s still a rare moment of naiveté for the band.

The actual lyrical content of “Hitsville U.K.” is a mixed bag. I really like the way the mini-chorus (“I know the boy was all alone ’til the Hitsville hit UK”) hits. It’s obviously adorable. I do really love the bit about “when lightning hits Small Wonder.” “It blows a hole in the radio when it hasn’t sounded good all week” does an awesome job climaxing the song in a moment of victory. “The band went in and knocked ’em dead in two minutes fifty-nine” is the clear winner, even though this song is 4:22. Still, there are a few clunkers. “No slimy deals with smarmy eels” in particular is really not very good.

But what of the music? Well, I think that’s the song’s main problem. Topping compares “Hitsville U.K.” to a couple of Holland-Dozier-Holland compositions, The Isley Brothers’ “This Old Heart Of Mine (Is Weak For You)” and The Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love,” and these comparisons do “Hitsville U.K.” no favors. The glockenspiel (played by Jones) isn’t seamlessly integrated, making the song sound like children’s music. Then there are the vocals.

After his breakup with The Slits’ guitarist Viv Albertine (as detailed by London Calling closer “Train In Vain (Stand By Me)”), Mick Jones got together with Ellen Foley, who was and still is most notable for her part in Meat Loaf’s epic duet, “Paradise By The Dashboard Light.”

Foley also had a solo career, with her 1979 debut being produced by Mick Ronson and Ian Hunter, the latter being lead singer of Mott The Hoople, Jones’ favorite band.

Though “Hitsville U.K.,” is often billed as a duet between Jones and Foley, Foley’s voice dominates, not just much louder in the mix but double tracked whereas I believe Jones’ is single tracked. Something about it just doesn’t work, though I’m not sure what it is. It might be that the vocal patterns themselves don’t play nice with the production. 2007’s The Sandinista! Project: A Tribute To The Clash has a cover by Katrina Leskanich (of Katrina And The Waves fame, famous for “Walking On Sunshine”) that sounds like a better approach, I think.

It could also be that Foley’s vocals don’t work for the song. It’s not like Foley doesn’t have a great voice. She sounds awesome on “Paradise By The Dashboard Light” and “Corner Soul” above. She’s probably a victim of circumstance.

In 1981, Foley released her second solo album, The Spirit Of St. Louis, recorded in July of 1980. It is loaded with talent from Sandinista!, with Mick Jones producing. The Blockheads who play on Sandinista! – Norman Watt-Roy, Mickey Gallagher, and Davey Payne – all show up. The four members of The Clash serve as the main backing band, with Jones having a major vocal part on “Torchlight.” Of the album’s ten original songs, Foley wrote one, Tymon Dogg wrote three, and six are credited to Strummer/Jones. It brings me absolutely no pleasure to report that I’m not much a fan of The Spirit Of St. Louis, which on paper should be an awesome Clash side project.